The Importance of Translational Research in Atherosclerosis– Crosslinking Studies from "Bench" to "Bed" and "Bunch"-sides Approaches

Last Updated: November 06, 2025

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the most important public health problem worldwide. Over the last quarter century, the global estimated age-adjusted mortality rates (/100,000 population) of CVD has decreased from 376 to 286,1, 2 but the mortality rate remains high, especially in developing countries, and this hinders the extension of healthy life span. Both the U.S. and Europe have updated their guidelines on the control of dyslipidemia to reduce CVD risk,3, 4 which previously emphasized the importance of LDL cholesterol lowering to prevent CVD. The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/ American Heart Association (AHA) 2013 guideline used the intensity of statin therapy as the goal of treatment rather than LDL or non–HDL cholesterol targets. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) /European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) 2016 guideline shows lipid goals as part of a comprehensive CVD risk reduction strategy including healthy diet, physical activity, normal weight, non-hypertension, non-diabetes, with a primary target of lowering LDL cholesterol. The EAS/ESC guidelines emphasize the importance of diet. Indeed, the PREDIMED (PREvención con Dieta MEDiterránea [PREvention with MEDiterranean Diet]) trial, for instance, showed that a Mediterranean type diet reduced the incidence of major CVD by ~30%,5 however, experimental trials for dietary patterns are very few, because such trials require a huge budget and the cooperation of many people to reduce or eliminate epidemiologic biases.

Whether therapy with pharmacologic inhibitors of proprotein convertase subtilisin–kexin type 9 (PCSK9) results in the predicted reduction in CVD events is being addressed in large outcome trials; when the 2016 European guideline was issued, preliminary evidence suggested that PCSK9 inhibitor therapy may be used either as monotherapy or in addition to the maximal statin dose.6 A meta-analysis showed that the variants in PCSK9 and HMGCR (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase) were independently and additively associated with approximately the same effect on the risk of CVD events and diabetes per unit decrease in LDL cholesterol level.7 Recently, the FOURIER (Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research with PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects with Elevated Risk) trial has shown that inhibition of PCSK9 with evolocumab on a background of statin therapy lowered LDL cholesterol levels to a median of 30 mg/dL (0.78 mmol/L) and reduced the risk of CVD,8 indicating that patients with atherosclerotic CVD could benefit from a lower LDL cholesterol level than the current therapeutic targets. In addition, the phase 2 ORION-1 trial, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multiple-ascending-dose trial of inclisiran has also shown that inclisiran use lowered PCSK9 and LDL cholesterol levels among patients with elevated LDL cholesterol levels.9 Professor Kausik Ray et al. commented that inhibiting the translation of PCSK9 mRNA in the liver represents an alternative to targeting circulating PCSK9 and would almost certainly involve a lower injection burden. It seems to be possible that an unheard-of treatment effect such as halving LDL cholesterol levels could come after half a year with two doses.10 Immunotherapy has become a major spotlight in the area of cancer. New treatments for immunotherapy are also expected in CVD. On the other hand, there are new questions to be examined such as insurance approval of monochromatic antibodies and side effects. Other areas such as bioethics and medical economics require further study.

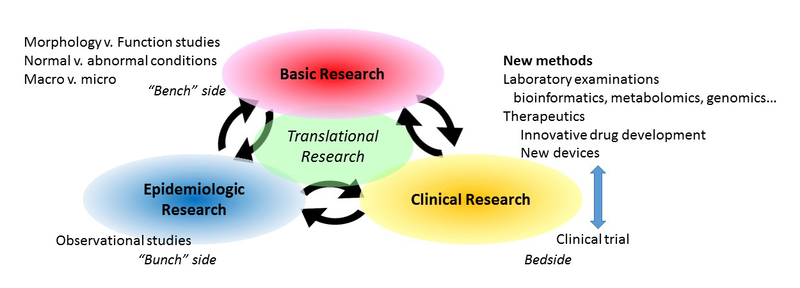

For such great exciting intervention studies and innovative drug developments, it is important to cross-relate clinical researches with basic and epidemiological researches in the field that has become known as translational medicine (see Figure). Just as clinical researchers study both basic medicine and epidemiology, it is very important for basic medical scientists to study clinical and epidemiological findings. For simplification, we refer to these three aspects of research as "bedside" (clinical), "bench"-side (basic research such as animal and in vitro studies) and "bunch"-side (epidemiological/ population studies). The new field of translational research combining these aspects benefits from new methods such as new laboratory examinations (such as bioinformatics, metabolomics, and genomics) and therapeutics (innovative drug development and new devices), as well as advanced database operation. For basic research, it is important to explore the relations of morphology–function, normal–abnormal conditions (such as histology and pathology), and micro-macro scale effects. As it is said that form follows function,11 uncovering the form can help reveal the function. Crosslinks between morphology and function are especially important for disease clarification. Epidemiologic perspectives are also important for basic and clinical medicine, that is, study design, sample size, and statistical method are all important issues informing both basic and clinical researches.

Recently, the writing groups of the American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, and the Council on Basic Cardiovascular Sciences presented the Recommendation on Design, Execution, and Reporting of Animal Atherosclerosis Studies: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. To my knowledge, this is the first comprehensive recommendation on how to conduct atherosclerosis studies in animal models. This publication is very useful in terms of providing guidelines for the development, execution and interpretation of experiments on animals, especially regarding the following three points: animal model selection for applications to human disease; experimental design and data interpretation; and standard methods to enhance accurate measurements and atherosclerotic lesion characterization. Despite the differences between human and animal manifestations of atherosclerosis, animal models help to develop understanding of the mechanisms of atherosclerosis. There are numerous fine points to consider when conducting animal atherosclerosis experiments; namely, animal model selection, experimental design, methodology, and interpretation and presentation of experimental data. Such points are summarized in this recommendation.

Obviously, we cannot directly apply research results from animal or cell experiments to a person, because even if significant results are obtained in animal and cell experiments, the results may not be found in humans. The mechanisms obtained in animal and cell experiments may simply not apply to human physiology, or there may be other confounding factors. Ideally, a study would be scrutinized and discouraged if such non-"translatable" results were likely to occur, so as to avoid wasting money, time and human resources, and to eliminate as much as possible the burden and side effects impacting the human subjects.

In order to provide clues for clarifying the disease state, animal studies must be rigorously designed and executed with data being interpreted within translational research from animals to humans. The Recommendation's authors, Professor Alan Daugherty et al., have offered a valuable work providing a framework for continuous animal research that assists in development of new and effective therapies for human health.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B, No. 16H05252) in Japan.

Citation

Daugherty A, Tall AR, Daemen MJAP, Falk E, Fisher EA, García-Cardeña G, Lusis AJ, Owens AP 3rd, Rosenfeld ME, Virmani R; on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; and Council on Basic Cardiovascular Sciences. Recommendation on design, execution, and reporting of animal atherosclerosis studies: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association [published online ahead of print July 20, 2017]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. doi: 10.1161/ATV.0000000000000062.

Daugherty A, Tall AR, Daemen MJAP, Falk E, Fisher EA, García-Cardeña G, Lusis AJ, Owens AP 3rd, Rosenfeld ME, Virmani R; on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; and Council on Basic Cardiovascular Sciences. Recommendation on design, execution, and reporting of animal atherosclerosis studies: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association [published online ahead of print July 20, 2017]. Circ Res. doi: 10.1161/RES.0000000000000169.

References

- Mortality GBD, Causes of Death C. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1459-1544.

- Mortality GBD, Causes of Death C. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385:117-171.

- Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:S1-45.

- Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, et al. 2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias: The Task Force for the Management of Dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016.

- Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1279-1290.

- Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2315-2381.

- Ference BA, Robinson JG, Brook RD, Catapano AL, Chapman MJ, Neff DR, Voros S, Giugliano RP, Davey Smith G, Fazio S, Sabatine MS. Variation in PCSK9 and HMGCR and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2144-2153.

- Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, Honarpour N, Wiviott SD, Murphy SA, Kuder JF, Wang H, Liu T, Wasserman SM, Sever PS, Pedersen TR, Committee FS, Investigators. Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017: DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1615664.

- Ray KK, Landmesser U, Leiter LA, Kallend D, Dufour R, Karakas M, Hall T, Troquay RP, Turner T, Visseren FL, Wijngaard P, Wright RS, Kastelein JJ. Inclisiran in Patients at High Cardiovascular Risk with Elevated LDL Cholesterol. N Engl J Med. 2017:10.1056/NEJMoa1615758.

- Couzin-Frankel J. Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2013;342:1432-1433.

- Wang C, Youle R. Cell biology: Form follows function for mitochondria. Nature. 2016;530:288-289.

Science News Commentaries

-- The opinions expressed in this commentary are not necessarily those of the editors or of the American Heart Association --

Pub Date: Thursday, Jul 20, 2017

Author: Yoshihiro Kokubo, MD, PhD, FAHA, FACC, FESC, FESO

Affiliation: Department of Preventive Cardiology, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, Suita, Japan, Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom